- Significant problem for dairy farmers during wet winter and early spring

- Manage water running onto the paddock before considering subsurface options

|

- Water does not have to appear on the surface for waterlogging to be a potential

problem

- Before considering draining a wet area you should contact your local Catchment Management Authority for advice, as a permit may be required

|

Understanding the problem

|

| Why is it important to me as a farmer?

|

- Waterlogging is currently a significant land degradation threat across much of south-west Victoria

- Vast areas including the Heytesbury Soldier Settlement and the Victorian Volcanic Plains represent landscapes significantly affected by waterlogging

- Is a significant problem for dairy farmers during winter and early spring where soils can remain waterlogged for considerable periods

- Causes poorer pastures, both in growth and quality

|

- Makes it harder and more unpleasant to farm, particularly for dairy farmers:

- those jobs with critical timing (such as silage making and crop sowing) can be upset

- tractors leave deep furrows in paddocks when feeding out

- cows pugging pasture to the point where they require a full renovation

- Waterlogging is also a major constraint to grain production in the region

|

- Waterlogging may be a natural condition of the soil, but can worsen with deterioration

in soil structure

- It occurs when rainfall exceeds the ability of some soils to drain surplus water away

- It is often perceived that waterlogging is a surface water problem that surface drains

will overcome. However, in many situations waterlogging is due to the soil profile (soil

below the ground surface) being saturated and some type of subsurface drainage

may be necessary to overcome this problem

- Unfortunately, some soils and areas, due to their location, cannot be economically or

feasibly drained by any means

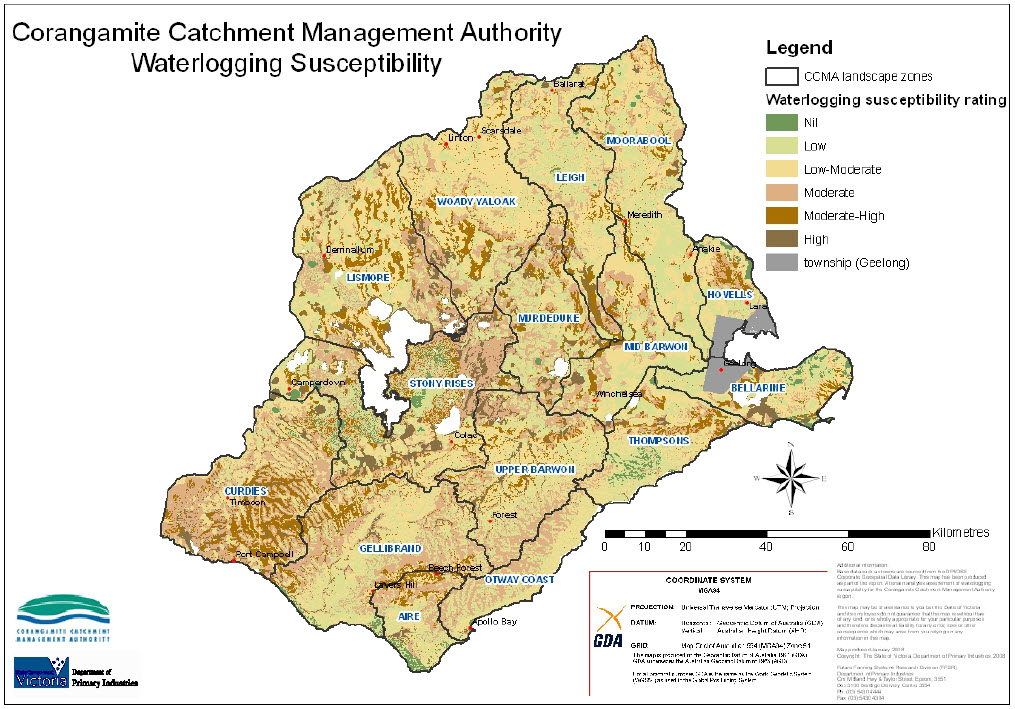

- Susceptibility maps indicate that waterlogging is high to very high over more than

50% of the Corangamite region and is:

- usually a seasonal problem

- caused by a relatively impermeable layer through which water moves only

very slowly

- due to soil compaction, sodic soils, high rainfall

- 'perched' water-tables in topsoil

Figure 1 - Waterlogging susceptibility in the Corangamite region (DEPI FFSR). - Source: CCMA

[View larger image]

|

- Generally located on low-lying heavy duplex soils in higher rainfall areas

- High to very high susceptibility to soil structure decline covers similar areas to

that of waterlogging, predominant in the south-west section of the region

- Waterlogging is common in the higher rainfall pastures of the region

particularly those on the clay soils of the Gellibrand Marl (Heytesbury) and

Basalt

|

| How to recognise it in the paddock

|

- Typically, waterlolgging can be easily observed on the soil surface, by the puddles as a result of perched watertables

- It is commonly associated with compaction, pugging, and sodic soils

Figure 2a : Waterlogging in the paddock. - Source: Soil Types and Structures Module, DEPI Victoria

Figure 2b : Waterlogging in the paddock. - Source: Soil Types and Structures Module, DEPI Victoria

- The effects on plants include:

- Reduced growth and yellowing or chlorosis of older leaves

- Damaged plant roots, resulting in restricted water and nutrient uptake by the plant

- Chlorosis of older leaves is observed due to poor root development and the consequential slow uptake of N by crop roots from the anaerobic soil

- Nitrogen deficiency symptoms (figure 3)

- Poor pasture utilisation by cattle

- The presence of weeds

|

Figure 3 : Loss of colour in older leaves of wheat indicating nitrogen deficiency. - Source: DAFWA

Figure 4 : Waterlogging can be detrimental to crop germination. - Source: Soil Types and Structures Module, DEPI Victoria

- If surface waterlogging is not clearly evident, the best way to identify waterlogged problem areas:

- Dig holes about 40 cm deep in winter and see if water flows into them. If it does, the soil is waterlogged

- Digging holes for fence posts often reveals waterlogging

- Some farmers put slotted PVC pipe (piezometers) into augered holes. They can then monitor the water levels in their paddocks

|

| What is the best practice?

|

Proper installation and maintenance of surface drainage (including raised beds) is critical

in minimising off-site impacts, especially where sediments and nutrients may enter

waterways and threaten water quality

1. Remove excess water (drainage options)

- Surface drainage - start with the perimeter

- Subsurface drainage

- Raised beds (cropping areas) - to reduce soil compaction and improve soil

structure

|

2. Minimise compaction (non-drainage options)

- Controlled traffic flat beds (cropping areas) - to reduce soil compaction and

improve soil structure

- Stock management - graze and spell (rotation) based on understanding of plant

and soil needs

- Land class fencing

3. Improve water storage in profile

|

| How can you achieve this?

|

1. Removal of excess water through drainage options

- Surface and sub-surface drainage is commonly used to rehabilitate waterlogged land and improve soil structure

- Currently, over 80% of dairy land has some form of surface drainage and up to 20%

has sub-surface drainage (MacEwan 1998)

Questions to ask yourself when planning farm drainage:

1. What is causing the waterlogging problem?

2. Does this happen each year or is it only a problem in very wet years?

3. Is there a sufficient outlet available?

4. What are the likely benefits of draining this area?

5. Which areas should be drained first?

6. What type of drainage system is required?

- Surface drains

- Subsurface drains

7. What are the non-drainage options?

8. Review the Water Act (1989)

Surface drainage - Is very useful in removing excess water from land in a controlled manner and as quickly as possible, to an artificial drainage system or a natural watercourse. This should be done with no damage to the environment.

Types of surface drainage include:

- These vary in size and length and can be formed by spinner cuts or excavators

- Must be very wary of constructing open drains in dispersive soil as they are highly prone to erosion

- These are usually shallow, varying in width from narrow to meters wide, but are constructed such that they are often grazed as part of the paddock

- They are sometimes used to bring drain outflows down slopes to prevent erosion without considerable expense

Humps and hollows (bedding):

- Hump and hollowing is the practice of forming (usually while renovating pastures) the ground surface into parallel convex (humps) surfaces separated by hollows. The humped shape sheds excess moisture relatively quickly while the hollows act as shallow surface drains

- Humps and hollows are useful in areas or on soil types that are not suitable for tile or mole drainage

|

Figure 5. - Humps and hollows in newly sown pasture. - Source: DEPI Victoria

Figure 6 : Good water management. - Source: Soil Types and Structures Module DEPI, Victoria

[View larger image]

Figure 7 : Poor water management. - Source: Soil Types and Structures Module DPI, Victoria

[View larger image]

|

Subsurface drainage - Once you have taken care of the surface drainage, you may need to look at improving the drainage through the soil profile. Subsurface drainage aims to take away only the surplus water in the soil. Therefore, you need to know what the soil type is before any works start.

Types of Subsurface drainage include:

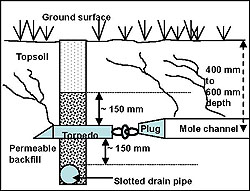

- Mole drains are unlined channels formed in clay subsoil by pulling a ripper blade (or leg) with a cylindrical foot (or torpedo) attached on the bottom through the subsoil. A plug (or expander) is often used to help compact the channel wall. The foot is usually chisel pointed

- Mole drains are used in heavy soils where a clay subsoil near moling depth (400 to 600 cm) prevents downward movement of ground water. Mole drains do not drain groundwater but removes water as it enters from the ground surface

Figure 8 - Mole drains over a collector pipe system. - Source: Managing Wet Soils: Mole Drainage

DEPI Victoria

- Gravel mole ploughs incorporate a hopper to allow finely graded gravel to fall into the mole channel. These ploughs have been used successfully in the UK in heavy soils that cannot hold 'normal' mole drains

- Experimental results from north east Victoria and Gippsland show they have promise on unstable clay soils, but are expensive because of the amount of gravel and close spacing needed. Unfortunately very few of these machines exist in southern Australia

|

- Over the past decade, extensive research efforts have been directed towards the factors that contribute to waterlogging and soil structure decline under broadacre cropping regimes. The biggest development has been with raised bed techniques, which currently cover about 10% of the annual crop area in the Corangamite region

- Raised beds aim to reduce machinery compaction by using controlled traffic and to reduce waterlogging by lifting the soil above the saturated zone. Where used, raised beds have significantly improved soil structure and reduced waterlogging on cropping land, while significantly increasing agricultural productivity in high rainfall areas

Figure 9 : Raised beds and a well planned grassed waterway. - Source: DEPI Victoria

- The Water Act (1989) provides guidance for the management of waterways and swamps. Before considering draining a wet area you should contact your local Catchment Management Authority for advice, as a permit may be required

|

2. Minimise compaction - non-drainage options

- Controlled Traffic

- to reduce soil compaction and improve soil structure

- Stock Management

- Change land use (dedicate as a hay or silage paddock and graze only in

summer, or remove from the grazing rotation)

- Remove stock as soon as pugging is imminent

- Allocate short grazing periods on restricted area to allow optimal feed intake prior

to onset of pasture damage - use 'on-off' grazing techniques:

- This refers to removing cows from the pasture after a short period of

grazing

- It has been identified as an effective method of reducing hoof compaction

on broadacre grazing land as it maintains good ground cover and higher

organic carbon levels

- This practice is currently being adopted over 30% of broadacre grazing

land in the Corangamite region (MacEwan 1998)

- Designate 'sacrifice area' to which cows are moved in any wet weather

- Construct or designate 'loafing area' (pad, laneway, barn or woodlot) to which

stock can be moved in wet conditions

- Construct feed pad for all supplementary feeding in wet weather

|

- Land Class Fencing

- Fence paddocks based on land capability and soil type

- It is easier to keep stock off wet areas if the paddock fences are located so that they separate the drier locations and soils from the wetter flat locations

- Consider land class fencing as a component of Whole Farm Planning

3. Improve water storage in profile

- By improving the water holding capacity of the soil it will reduce the likelihood of

waterlogging. A good surface structure with no surface crust will ensure the rain

gets in. The topsoil structure is improved by:

- increasing soil organic matter levels

- reducing tillage

- increase amount of surface cover to reduce the amount of surface sealing

on the soil - this also assists in reduction of water loss through

evaporation

- use of raised beds

- adding gypsum

|

Other related questions in the Brown Book

|

|

Brown Book content has been based on published information listed in the Resources and References sections below

|

- Clarkson T, Department of Primary Industries on behalf of the Corangamite Catchment

Management Authority (2007).Corangamite Soil Health Strategy 2007.. Corangamite

Catchment Management Authority, Colac, Victoria.

- MacEwan R. (2003). Soil Health Strategy for Corangamite Region. (Discussion paper).

Centre for Land Protection Research.

- MacEwan R (1998) Winter Wet Soils in Western Victoria - Options for the Dairy Industry. WestVic Dairy Research and Development Committee and the University of Ballarat.

- Johnston T (2011), Soil Types and Structures Module. Victorian Department of Primary

Industries.

- Hopkins D (1998) and Mikan F. (2008). Planning Farm Drainage. (AG0942) - Department

of Primary Industries Victoria.

|

- Mikan F. (2010). Managing Wet Soils - Mole Drainage. (AG0949) - Department

of Primary Industries Victoria.

- Mikan F. (2010). Managing Wet Soils - Surface Drainage. (AG0946) - Department

of Primary Industries Victoria.

- Department of Primary Industries Victoria - Future Farming Systems Research (2008). A

terrain analysis assessment of waterlogging susceptibility for the Corangamite CMA

region. Report ORL 1.1 (MIS05188). Published for the Corangamite CMA.

- Peries, R., Wightmann, B. And Bluett,C. (2004). Soil structure differences under raised beds GRDC Hi-Grain Update, September 2004.

|

|