| How do I improve soil without using

too much fertiliser?

|

- Assess current soil conditions and identify key constraints to production before developing your nutrient management plan

- Farmers make soil and nutrient management decisions with imperfect knowledge. Decisions are based on the best available science and their own and other people'sexperience

- The general approach is to take account of the main nutrients entering and leaving the farm and allowing for the influence of soil factors when working out what fertilisers are required

- The key to cost-effective fertiliser management is to make sure that the fertilisers you are applying match the nutrient requirements of your farming system

- Nutrient planning uses the concepts of capital and maintenance to determine the nutrient requirement on different areas of the farm

|

- Target levels of soil fertility should be set based on your production system

- Monitoring soil fertility with soil tests is a vital step in the nutrient planning process

- Approximately 10% of agricultural land managers in the Corangamite region regularly conduct soil tests to determine the nutrient input requirements for the soils

- Many land managers could potentially be applying insufficient or excessive amounts and/or the incorrect type of fertilisers to their soils

- Continued levels of agricultural productivity depend on good soil health, focusing on soil chemical, physical and biological condition

- Increasing soil organic carbon levels through the modification of management practices and complementing inorganic fertilisers with organic fertilisers will contribute to a more sustainable production system in the longer-term

|

Understanding the question

|

| Why is it important to me as a farmer?

|

- Maintaining a cost-effective balance of available plant nutrients is an important

component of farm management. Sustainable land use requires the replacement of

extracted nutrients. Nutrients can also be lost from the soil through leaching into the

deeper soil profile, in run-off or through soil movement

- In some cases, nutrient extraction or deficiencies may be over-corrected through

excessive fertiliser or trace element application leading to unnecessary expense for the

farmer as well as unintended off-site impacts to the environment

|

- The key to cost-effective fertiliser management is to make sure that the fertilisers you are

putting onto the paddock match the nutrient requirements of your farm and enterprise. If

this is done, only the nutrients that are required for plant growth are applied

- Too often money is wasted on fertilisers that contain nutrients that are already at high

levels in the soil. The rewards are there in either cost saving or improved productivity for

those who take the time to work out their actual farm fertiliser requirements before they

place the fertiliser order

|

| Background information about fertilisers

|

- A fertiliser or soil conditioner is any material added to the soil or applied to a plant to

improve the supply of nutrients and promote plant growth. This definition includes both

inorganic and organic fertilisers and also soil conditioners, such as lime and gypsum,

which may promote plant growth by increasing the availability of nutrients that are

already in the soil or by changing the soil'sphysical structure

- Most soils contain reserves of nutrients that would otherwise have to be applied in

fertilisers

- Most soils throughout the Corangamite region are naturally deficient of the level of nutrients required for agricultural production

- In addition, the decline in soil carbon has resulted in a further decline in the natural fertility of the soils

- As a result dairy, cropping and broadacre grazing managers apply fertilisers to improve productivity

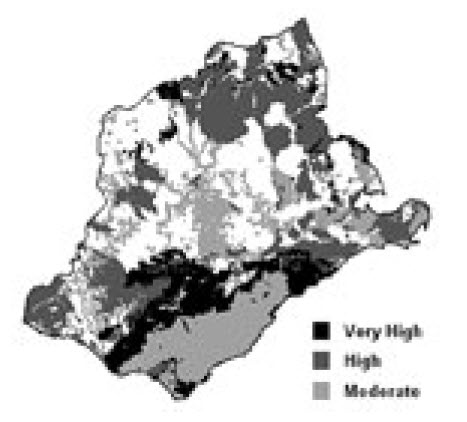

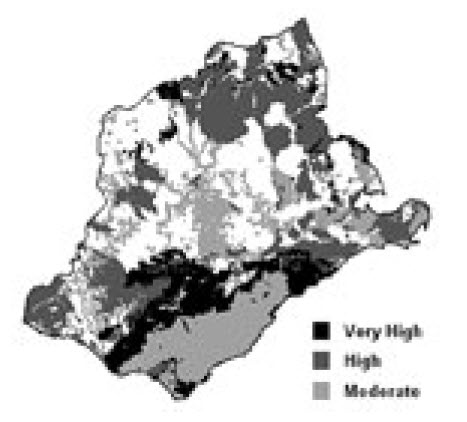

- Nutrients are replaced as they are removed from the soil by pastures and crops. The greatest susceptibility to soil nutrient decline is found along the ranges of the Otways

Figure 1 - Areas of moderate, high and very high soil nutrient decline susceptibility in the

Corangamite region. - Source: CCMA Soil Health Strategy

Figure 1 - Areas of moderate, high and very high soil nutrient decline susceptibility in the

Corangamite region. - Source: CCMA Soil Health Strategy

|

- The nutrient requirements of a farm depend on many factors, including:

- Soil type

- Current soil nutrient status (affected by soil parent material, fertiliser history,

climate, stage of farm development)

- The target soil nutrient levels you have set

- Your farm production system (class and number of stock to be fed, amount of

milk to be produced, amount of fodder conservation or cropping, etc.)

- Rainfall

- These factors must be taken into account when making fertiliser management decisions

on your farm. As these factors are variable, nutrient requirements will vary from farm to

farm, paddock to paddock and year to year on fertilisers that contain nutrients that are

already at high levels in the soil. The rewards are there in either cost saving or improved

productivity for those who take the time to work out their actual farm fertiliser

requirements before they place the fertiliser order

- We often view fertiliser applications and the 'build up' in soil fertility in terms of capital

and maintenance applications. Simply put:

- Maintenance applications are applied to keep the soil nutrient status at the same

level while supporting pasture and animal production

- Capital applications increase soil fertility to a target level. It is important to

remember that capital applications are the nutrients that are applied in excess of

the maintenance requirement for any given production system

- The concept of capital and maintenance nutrient applications is used to estimate your

farm fertiliser requirements. If a maintenance application is spread annually, assuming

stocking rate and other parameters do not alter greatly, soil fertility will remain at a

similar level over time. If a capital application is made, soil fertility will increase over time

|

Table 1 - Fertiliser characteristics : manufactured and organic/natural. - Adapted from the

Soil Knowledge Bank - Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry

|

| |

|

What are they made from? |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

| |

Manufactured (inorganic) fertilisers |

Produced synthetically from treated raw materials |

- Most contain inorganic nutrients that are readily available to plants (soluble)

- Supply can be better controlled than in organic fertilisers

- Compound fertilisers contain N, P and K, and may contain useful amounts of other nutrients

- Slow nutrient release reduces leaching potential

- Helps maintain soil structure when used in sufficient quantities

|

- Their solubility can cause problems

- Nitrate, for instance, is easily leached through the soil into groundwater

- High energy cost to produce

|

| |

Organic fertilisers

i.e. plant composts, composted manures and animal byproducts |

Derived from decomposed or digested plant and animal matter

|

- Continued release of nutrients throughout growing season

- As soil organisms break the organic matter down, they produce a relatively stable form of organic matter called humus

- Humus is important in binding soil particles, promoting water entry, holding plant nutrients and buffering soil pH

|

- Nutrients in the organic form must be converted by microorganisms in the soil to inorganic form before they can be taken up by plants

- As a result they are often released at a slow and uneven rate

- Nutrient content varies greatly depending on the fertiliser source, making it difficult to predict their effectiveness or cost per unit of nutrient

|

| |

Naturally occurring fertilisers |

Minerals found in nature that contain valuable plant nutrients |

Long term maintenance |

Generally much less effective than water soluble fertilisers in meeting short-term needs; can have a good residual effect |

| What is the best practice?

|

- Use of soil test and nutrient planning tools to develop a nutrient budget

- Maximising root abundance and rooting depth (cropping)

- Optimise fertiliser application

- Encourage a healthy soil ecosystem

|

|

| How can you achieve this?

|

1. Use of soil test and nutrient planning tools to develop a nutrient budget

- 'Nutrient budgets', together with soil tests, are recognised as prime indicators for

improved nutrient management

- Soil tests should be used to identify whether topsoil nutrient levels are at, above

or below the target ranges

- It is not practical to soil test every paddock on the farm but it is reasonable to

expect that different parts of the farm will have quite differing soil test results at

any one time. We need to think of the farm as a grouping of soil management

areas, where a representative soil sample would be taken from each area

- On areas where nutrients are below the target levels, capital applications of

nutrients are required

- Once target levels are reached, maintenance fertiliser rates should be applied

- The aim of nutrient budgeting is to balance inputs and outputs, so that levels are

maintained at the optimum for production

- Maintenance nutrient requirements will be different on different areas of the farm

due to variations in soil type and fertility

|

- Differences in other imports and exports, such as differences in production levels

or where brought-in fodder is fed out, will also result in a variation in maintenance

requirement between paddocks across the farm

- Nutrient budgeting on a whole-farm basis gives only the big picture of what is

happening at a farm gate level. It is very useful for indicating whether some

nutrients are being overapplied or underapplied. For example, is more P or K

being brought into the farm than is required for production? However, the farmer

must ultimately be able to manage the nutrient balance down to individual

paddocks or at least areas

- Farmers need to understand how to calculate the rates of fertiliser or individual

nutrients to be applied and how to calculate the cost of various fertiliser options.

Although this can be carried out by the fertiliser company, farmers who can do

their own calculations can check the company'srecommendations or can make

their own recommendations

Use of nutrient planning tools to guide you through the determining the total nutrient

requirements of the farm

|

Table 2 - Summary of the fertiliser planning process. Nutrient Planning - Department of Environment and Primary Industries, Victoria

|

| |

1 |

Gather up as much information for your farm as you can: |

| |

|

Soil tests, tissue tests, paddock history, production, brought-in feed. |

| |

|

Putting soil test results onto the farm map is a good way to map out soil types and

different management areas over time |

| |

2 |

What are your soil tests telling you? |

| |

|

What else may be limiting growth (pH, species, waterlogging etc.) and should these

factors be fixed first? |

| |

|

What are the nutrient levels in the soil around the farm? |

| |

3 |

How many fertiliser applications are practical, and what will be the timing of

application? |

| |

|

Will you treat areas differently (soil types, history, different fertility)? |

| |

|

Will you use split applications (autumn P, K & S, spring K, S)? |

| |

4 |

What are your maintenance and capital nutrient needs for this year? |

| |

|

Calculate this for each area you will treat differently |

| |

|

Maintenance + capital (if required) = total requirement |

| |

|

Use NutriMatch nutrient budget sheets or other tools. |

| |

|

Maintenance: What is required to keep levels where they are? |

| |

|

Capital: Do the levels need a boost? Which areas? Over what timeframe? |

| |

|

Can you cut back if levels are high? |

| |

5 |

What products will you use? |

| |

|

Once you have the total nutrients to be applied over the year to different areas, try

to work out some products. Use the nutrient analysis that matches the ratio of

nutrients to apply. Use look-up tables and product lists, consider designing a blend,

and seek advice from fertiliser reps |

| |

|

Use advice from fertiliser reps to apply the nutrients at a lower cost. Ask them about

the products you have come up with |

| |

6 |

What products will you use? |

| |

|

Check that maintenance levels (plus capital if desired) are being met every year |

| |

|

Monitor with soil tests |

| |

7 |

Consider finances |

| |

|

If costs are an issue, apply maintenance then build up when finances are not so

tight |

2. Maximising root abundance and rooting depth (Cropping)

- One way to optimise plant uptake of nutrient reserves in soil is to maximise root

abundance and rooting depth. This means that crop roots can explore more soil

and ensures they can follow nutrients and water down the profile

- This is especially important for leachable nutrients such as nitrogen and sulphur

and nutrients with significant reserves in the subsoil

- Root abundance and rooting depth can be increased by maintaining optimum soil

pH and minimising soil compaction and plant root diseases

3. Optimise fertiliser application

- The rule to remember with soluble fertilisers is to apply small amounts regularly,

rather than a large amount occasionally. Plants can use only a fraction of any

large amount applied, so most will be leached away or react with the soil (P, Cu,

Zn, etc). This is not only a waste of fertiliser and money, but it may also pollute

ground water and surface waters and may contribute to the development of algal

blooms

- Organic fertilisers can be applied in larger amounts less often, as they release

nutrients more slowly, but you still need to be careful how you use them

|

- Non-mobile nutrients such as P stay close to where they are applied, and are

moved only by cultivation and seeding. Fertiliser placement should be used to

ensure optimum plant uptake during growth and development, and P should be

positioned where it is likely to be in moist soil for longer

- Fertilisers should NOT be applied to:

- bare soil (except when sowing)

- waterlogged soils

- drainage lines, riparian buffer areas and waterways

- stock camps

- paddocks or drainage depressions when rainfall that could result in runoff is expected, (e.g. when summer storms are anticipated in the next few days)

- some native grass species

4. Encourage a healthy soil ecosystem

- Increase soil organic carbon

- For example you could use manure, plant debris and composts. Some of these recycled organics also contain significant amounts of nutrients and can act as organic fertilisers and soil conditioners

- Use soil friendly agronomic practices

- When sowing use direct drilling

- Reduce soil compaction

- Increase soil biodiversity

|

Other related questions in the Brown Book

|

|

Brown Book content has been based on published information listed in the Resources and References sections below

|

- Introducing Fertilisers. Department of Primary Industries, Victoria.

- How do I manage soil fertility? - Soil Health Knowledge Bank - Department of

Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry.

- Clarkson T, Department of Primary Industries on behalf of the Corangamite Catchment

Management Authority (2007) Corangamite Soil Health Strategy. Corangamite

Catchment Management Authority, Colac, Victoria.

|

- Sustainable land management practices for graziers. 3 Managing Soil Fertility,

Department of Primary Industries, NSW.

- Optimising Soil Nutrition. factsheet - Soilquality.org.au.

- Greenwood,K., Rees,D., Davey,M. and Brown,A.(2008) - Final report to Dairy Australia on DAV 12222, HDLN Soil and Water Dairy Action Program - Soil Assessment Component. Department of Primary Industries, Victoria

|

|  Figure 1 - Areas of moderate, high and very high soil nutrient decline susceptibility in the

Corangamite region. - Source: CCMA Soil Health Strategy

Figure 1 - Areas of moderate, high and very high soil nutrient decline susceptibility in the

Corangamite region. - Source: CCMA Soil Health Strategy